Bill English is quoted in the Herald today as saying, a propos of rising house prices and low housebuilding numbers:

It’s clear that the lowest-income households have been the most affected so our planning processes have probably done more to increase income inequality in New Zealand than most other policies and it does remain a challenge to make progress.

But while it is true that housing does have an impact on inequality, I’m not sure there’s evidence to justify that claim.

Rising housing costs are affecting people on low incomes, certainly. The international standard is that no one should spend more than 30% of their income on housing costs, otherwise there just isn’t enough left for other things. But the percentage of New Zealanders spending more than that on housing has risen from 11% in the 1980s to 27% now. Most of these will be the poorest New Zealanders.

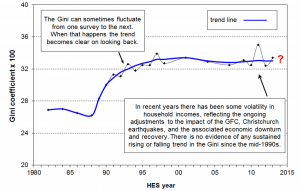

So when you look at the figures on inequality produced every year by the Ministry of Social Development, it’s clear that housing costs do make inequality worse. But – and this is the real problem for English’s argument – inequality is already very high, and has risen hugely since the 1980s, even before housing costs are taken into account. It’s not at all the case that, if you took housing out of the equation, everything would be hunky-dory. In fact, the gaps caused by other things swamp the gaps caused by housing.

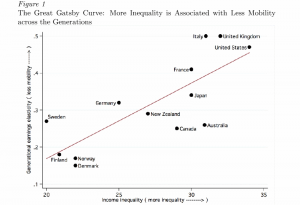

So it seems unlikely that New Zealand’s planning processes have “probably done more” to increase inequality in any other. Far more important factors, in my opinion, would include reduced taxes on top earners, lower benefits, weaker union bargaining power and the influence of globalisation and technology.

And, even if you think housing is driving inequality, it’s not clear that planning processes and councils are to blame. Well over 90% of resource consents are processed without any notification or anything else to slow them down. And council development charges make up a fraction of housing costs. The bigger problems are likely to be the fact that we have almost no firms that build more than 100 houses a year, so hardly anyone can get economies of scale to drive down prices; and local opposition (as I see locally in, say, Johnsonville) to building more in urban centres.

Wealth inequality

As a final note, English’s argument ironically points to facts that his opponents, notably Labour’s David Parker, want to stress.

One of the big things that has probably happened in the last decade is a major increase in wealth inequality, in terms of the assets that people own.

Fewer and fewer people own their own home; those that do have seen the value of those homes increase sharply. Since half of all our assets are held in the form of housing, this (along with other things) means that wealth inequality has almost certainly been increasing (although we haven’t been measuring, so it’s hard to be sure).

Anyway, this is the point that Parker makes every time English claims that inequality isn’t getting worse. Inequality of income may have been relatively flat in the last few years, but inequality of wealth probably hasn’t.

In other words, talking about housing as a contributor to inequality may not help English as much as he thinks it does.

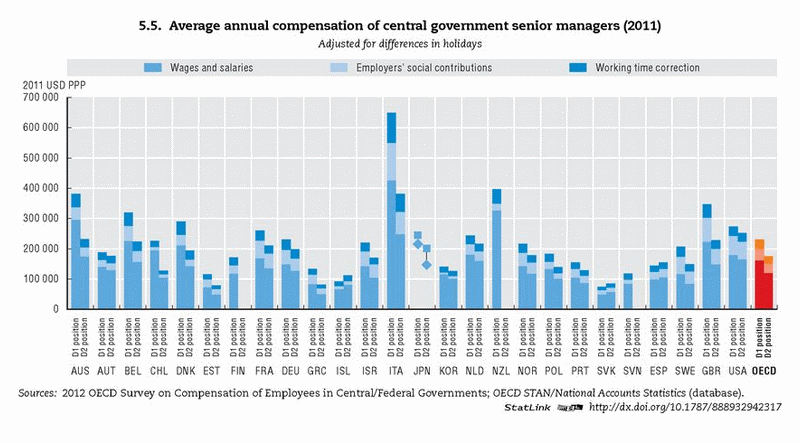

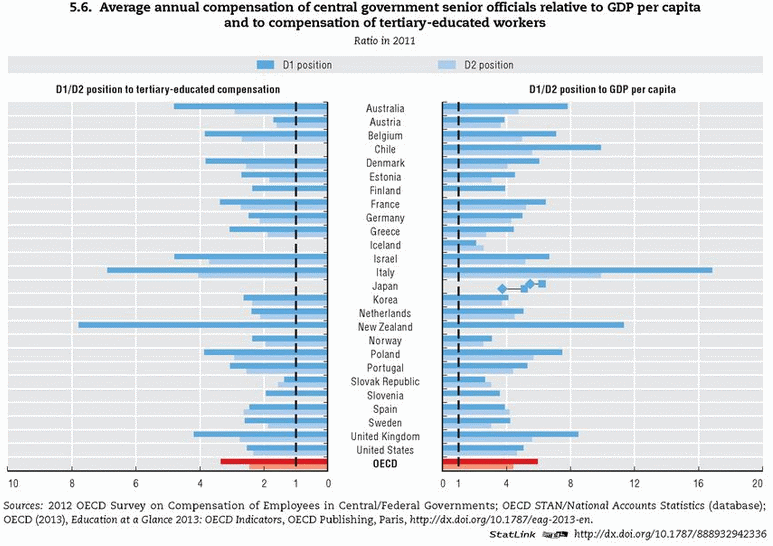

ort, shows the average chief executive in a New Zealand government department earned US$400,000 in 2011. Only in Italy, where average pay was a stratospheric US$650,000, did public sector chief executives do better. What’s more, if you compare the pay of chief executives with those of other people with university qualifications, as in the chart below, New Zealand’s government CEOs are the highest-paid in the world.

ort, shows the average chief executive in a New Zealand government department earned US$400,000 in 2011. Only in Italy, where average pay was a stratospheric US$650,000, did public sector chief executives do better. What’s more, if you compare the pay of chief executives with those of other people with university qualifications, as in the chart below, New Zealand’s government CEOs are the highest-paid in the world. the question is how can we have such high pay rates, in a country that is small by international standards?

the question is how can we have such high pay rates, in a country that is small by international standards?