On Wednesday the New Zealand Council for Christian Social Services (NZCCSS) hosted an event on inequality and the Budget with ministers Bill English and Paula Bennett.

Perhaps the most telling phrase came from English, when he said that, in his view, a lot of the debate around inequality was “true, but useless”.

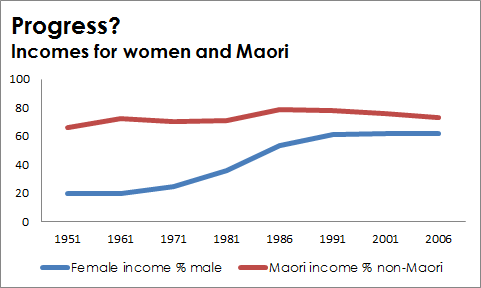

This implied that, while it’s true that inequality has risen significantly in the last 30 year, there’s no point worrying about income gaps, just absolute poverty and “persistent deprivation”.

It was a shame the ministers couldn’t stick around for the NZCCSS presentations, which argued that the two things are inextricably linked: people’s incomes are so low because we have an economic system in which a lot of the rewards of their hard work are being channelled upwards into the arms of the richest 10%.

English didn’t see a connection, however, and focused instead on policies like free GP visits being extended from age 6 to age 13, which he argued would make a significant difference, and help reduce hospital admissions, for a cost of just $30 million a year. (The low pricetag, English admitted, might be in part because “kids between six and 13 don’t go to the doctor much”.)

The government was also asking itself what it should do with the expected welfare savings from more people moving into work, and whether they should be “recycled” back into more active support for those still on benefits.

In what looked like an admission that benefit levels and other supports are too low, English said: “At the bottom level, quite apart from the benefit levels, we under-resource them [families in poverty].”

Interestingly, he insisted that fiscal discipline and taking a tough line on beneficiaries was necessary to generate support for more welfare spending. The government had to show middle New Zealand that “putting more money in won’t make the problem worse”, and people would develop “a stronger, broader empathy” for beneficiaries only if they felt that was the case.

But again, if the ministers had stuck around, they would have heard the argument that the biggest destroyer of empathy in a society is, in fact, inequality, since people with very different incomes and lives find it hard to empathise with each other.

The ministers did hang around for questions and comments from the audience – and were promptly told that providers of social services in New Zealand were “in crisis” thanks to frozen funding and increased reporting burdens. They were also urged to work in a closer partnership with providers, allowing agencies to help shape strategies, not just deliver them.

However, the ministers showed significant frustration with any talk of partnership. English said the government was “not here to service the NGO [non-governmental organisation] sector”, while Bennett said, “We can come up with some agreed language if that makes you feel better.”

English also made clear his frustration with the public sector, especially over cross-agency collaboration. Joint working on children’s teams, for instance, was being held up by “discussion on whether the policeman will be told what to do by the nurse. I’m sick of hearing this … [from] well-paid people, with good jobs, getting paid good money.”

If re-elected, English said National would be “reasonably energetic about trying to move these things on. We can’t sit around letting the deliverers get in the way for too long.” In what sounded like a willingness to privatise more services, he said: “The nurse and the policeman will have to sort out their differences … or we will get someone else to do it.”